West Haven, CT, July 6, 2016 (Newswire.com) - Curriculum development models are similar in concept, but Kern’s 6 Step Model (Kern et al, 2009) provides a great framework for tackling education in healthcare. Although most people have a natural inclination to jump to educational methods (i.e. which scenario should I do), I spend 60-70% of my time on any curriculum in the area of Problem Identification. Spending that much time in problem identification is intentional as it puts the focus on what problem we are trying to solve, which will naturally answer what outcome should we measure.

A quick review of the Kern 6 Step Model: (buy the book, it is well worth it http://tinyurl.com/kern6 )

Problem identification is at the core of improving healthcare outcomes through learning.

Jay Zigmont, Learning Innovator/Founder

- Problem Identification and General Needs Assessment

- Needs Assessment and Targeted Learners

- Goals and Objectives

- Educational Strategies (content and method)

- Implementation

- Assessment or Evaluation (outcomes)

Kern’s model intentionally is drawn as a circle, as it is not a linear pathway, but it is much easier to start with problem identification than to look at an educational strategy and try to figure out what problem it solved. Unfortunately, the later is common. For example, I am often asked something along the lines of, “I have been doing mock codes for years, how do I determine a measurable outcome?” My response is simply, “well, what problem were you solving,” and we may get stuck in a discussion about how someone wanted to use simulation for codes, and it was a good idea, rather than actually solving a problem (such as extended time to defibrillation or negative patient outcomes).

Some have difficulty with the word ‘problem’ and you can feel free to substitute it for opportunity. The intent is to identify a gap between the current and ideal approaches, and then find ways to improve it. The start can literally be a problem (such as what was identified by a root cause analysis) or can be more of an opportunity (i.e. improve from x to y). A good rule of thumb is that at the end of the problem identification, you should be able to set a goal in the format of from x to y by z (time). Having a compelling goal is one of the Four Disciplines of Execution (good book to read available at: http://tinyurl.com/hjgft94 ), which will help to keep you focused on the wildly important goal of fixing a problem

It may be easier to start with things that aren’t a problem: e.g.

- I want to do a simulation on… (not a problem, this is a potential solution)

- My Dean says I should do simulation… (not a problem, it is an opportunity and demonstrated buy-in)

- I have 8 hours and want to fill it… (not a problem, and probably the worst way to start creating a curriculum. Filling time means we are focused on butts in seats, and goes against the core Principles for Learning in Healthcare (Learning Card 10)

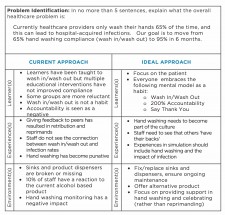

The first step is to simply (less than 5 sentences) explain what the healthcare problem is. The simpler you can make the statement, the better. Unfortunately, coming up with a simple statement of a healthcare problem can in itself be difficult. To provide an example, we will use one of my favorite healthcare problems, hand washing. A problem statement may go like this:

Currently healthcare providers only wash their hands 65% of the time, and this can lead to hospital-acquired infections. Our goal is to move from 65% hand washing compliance (wash in/wash out) to 95% in 6 months.

Technically setting the goal comes later in the process, but if you have a baseline identified in your problem identification, then it is easy to develop a goal at the same time (and this is OK).

After a general problem statement is developed, the next step is to identify factors in each: the Learner, Experience and Environment (Learning Card 1) that needs to be addressed in order to achieve the goal or fix the problem. The challenge for educators is to think past the classroom or simulation center, as this is essential in order to improve outcomes (Learning Card 10). An example might be as follows: If we teach everyone to wash in and wash out, but the sinks are broken, then our initiative will fail. The converse is that, putting out a policy or letter about washing your hands is not enough to change behavior.

The ‘product’ of the problem identification process may look simple, but in this example, it took a team at a hospital almost six months to complete. The work was worth it as the end result was ~90-95% compliance after 9 months, and sustained for the past two years. The ‘education’ initiative had to do with spreading the word on the new “200% accountability pledge” (based on work from the Influencer Model http://www.amazon.com/Influencer-Science-Leading-Change-Second/dp/0071808868/learn0f6-20 ). Managers spread the word to their team, and held all caregivers responsible to the pledge. Simply put, if someone said, you did not wash your hands, you washed them and said thank you. The 200% accountability meant that we have each other’s backs, and appreciate their support.

Diagnosing a problem takes skill and tools. There are multiple tools within the learning cards that can help you including:

- Learning Outcomes Model (Learning Cards 1, 2, 3, and 4)

- Stages of Competence (Learning Card 9)

- 5 Whys (Art of Questioning, Learning Card 13)

- Focus Groups (Learning Card 12)

- Identifying Mental Models (Learning Card 14)

- Learning vs Management Problems (Learning Card 17)

- Learning vs Quality Cop (Learning Card 18)

The best place to start is with the 5 Whys and Focus Groups. Your intent should be to be truly curious about what is going on. To get to the core of the problem, you may need to take a ‘360 approach’ and interview/question different types of stakeholders (in the above example that included staff (nurses, physicians, others), management, and quality/safety). Those who are familiar with qualitative research will find that many of the core skills used in ‘generic qualitative research’ are at the center of problem identification. Numbers are useful for measuring current and future state, but may not be able to explain the why, which is at the core of the problem.

To provide a medical example, problem identification is the process of diagnosing the patient before treating them. There are multiple diagnostic tools, but we all agree that diagnosis comes first. In education, we often jump to the ‘treatment’ (i.e. everyone needs an online course on hand washing) without doing the diagnosis (problem identification). The result is that we are often treating the wrong problem (in medical terms it would be like giving every patient broad spectrum antibiotics, which has its own side effects and will not help every patient).

Kern, DE, et al: Curriculum Development for Medical Education – A Six-Step Approach. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Univ. Press. 2009

. . .

This part of a series called "Learning That Works" by Jay Zigmont, Ph.D., CHSE-A (jay.zigmont@gmail.com ). For a video on this topic and more information, visit http://L11.LearningInHealthcare.com . The principles above are part of the core content (Learning Card 11) of the Foundations of Experiential Learning Manual (http://FEL.learninginhealthcare.com ).

Source: Learning in Healthcare

Share: