West Haven, CT, June 15, 2016 (Newswire.com) - Debriefing is an expertise to develop, hone and focus on as an expertise. Skilled debriefers can debrief most anything, and learners will walk away with new mental models that change their practice. Becoming skilled in debriefing requires deliberate practice (Ericsson, 1997), and the often-quoted 10,000 hours to become an expert. We may not all have 10,000 hours to dedicate solely to debriefing, but we can all deliberately improve our skills in debriefing.

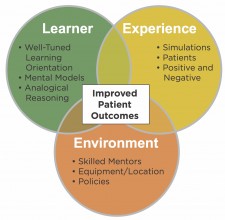

Debriefers use different models, but at their core, debriefing is mostly the same. In this two part series, we will use the 3D Model of Debriefing: Defusing, Discovering and Deepening (Zigmont, Kappus & Sudikoff, 2011a) but the basics apply to most models. The 3D Model was created to reflect Experiential Learning (Kolb, 1984) and the Learning Outcomes Model (Zigmont, Kappus & Sudikoff, 2011b) to improve healthcare outcomes. Debriefing itself is more than reflection after an experience and needs to take into account the learner, their experience, and environment (Zigmont, Kappus & Sudikoff, 2011b).

Effective debriefing needs to consider the learner, their experience, and environment. Developing effective debriefing requires deliberate practice.

Jay Zigmont, Learning Innovator/Founder

Any learning initiative needs to start with setting a psychologically safe learning environment. Rudolph, Raemer & Simon (2014) did a great review entitled "Establishing a safe container for learning in simulation: The role of the presimulation briefing" which has become a must-read for all debriefers. As a basic primer, here is a list of considerations for creating a safe learning environment:

Ensure that the environment is physically safe. Debriefers should orient learners to the room, know which equipment is ‘live' (such as defibrillators), how to call for help, and what the ‘safe word' is. Best practice is to set a safe word for all simulations (such as, orangutan) that when spoken, will stop all actions in case of safety issues (and to clue learner when a safety issue that occurs is not part of the simulation).

Invoke the ‘Vegas Rule'; what happens in simulation stays in the simulation. Learners need to know that it is OK to make mistakes, and they may hurt them. In healthcare organizations, debriefers may have to invoke the ‘Vegas Rule, But…'. The ‘but' is that if you are blatantly unsafe or against service expectations, we may have to share your experience with your boss for patient safety. The debriefer should always tell the learner the Vegas rule must be broken and what you are going to tell their boss in case of a safety issue.

Be sure to let learner know if they are being ‘tested.' Anytime summative assessments are completed in simulation, learners need to know in advance. If debriefers, or their organization, are keeping track of their performance for use against a grade or further action, then the learner is being tested, and it is not truly Vegas.

Invoke the fiction contract and orient the learners to all simulation equipment. The fiction contract states that the simulation center does the best they can to make the environment real, but the students need to buy-in. Orientation to the manikin and environment should explain the limitations and where learners will need to buy-in. If you are using simulated patients, be sure that the students understand what procedures can and cannot be done on them and what they may have to ‘fake'.

As students start having simulation experiences elsewhere, debriefers may also have to take time during pre-briefing (setting the environment) to talk about the differences from their previous experiences. In some cases, their previous experiences may have ‘scarred them' to a point where they have an emotional reaction to simulation. Being aware of students' previous experiences will help debriefers make sure they feel psychologically safe in their current environment and know the differences from their previous experiences.

In addition to setting the immediate learning environment (lower case e), debriefers need to assure that the practice Environment (capital E) is set for learning if we want to improve outcomes. The practice Environment needs to have appropriate equipment, policies, and skilled mentors to assure that what learners gain in simulation continues over to practice. If the practice Environment differs significantly from the learning environment, then the learning may be ‘lost' in translation.

Setting a psychologically safe environment will help learning, but the bottom line is that adults learn what they want to learn when they want to learn it (Knowles, 1985). Ensuring the learner has a willingness to learn will change both their participation level and the likelihood of translation to practice. Although some individuals may never be interested in learning, there are a few steps debriefers can do to set the learner up for success:

Ensure that any experiences and debriefings have a direct connection to practice. Adjusting debriefing timing and topic to reflect the learners' current needs will help increase buy-in; for example, provide the psychiatric patient scenario just before the learners do their psychology rotation.

Ensure that experiences are not ‘punitive'. Some sites have used simulation for when a learner does something ‘wrong' in clinical. The result is that learners start thinking of simulation as ‘going to the principal's office' and tune out all experiences.

Teach individuals how to learn from their experiences. Help learners to understand their experiential learning style (Kolb & Kolb, 2005) and how to make the most of the simulation. Learning from experience is a skill that simulation can help teach that will help learners across their entire career.

Focus on few formal objectives (2-3) and allow the learner to identify their own. Limiting formal objectives and allowing the learner to identify their own will prompt deeper learning and allow the learner some control (increasing their willingness to learn).

Respect the learners' experience. Simulations should allow learners to put together what they do know, or identify what they do not know. Adults come with their experiences (Knowles, 1985) and should be encouraged to bring them to the debriefing table.

Focus on developing mental models rather than adding facts. Experience allows individuals to build both tacit and explicit mental models for use in practice (Gentner & Holyoak, 1997). The focus of debriefing should be on helping the learner understand their mental model and how to improve it for future experiences.

Resist the urge to ‘save' the learner, allow them to make mistakes in a safe environment. If the environment is truly safe (psychologically and physically) then it is OK to let the learner make mistakes. Individuals learn better from their mistakes, as mistakes are experiences that cause a change in body state (Damasio, 1997).

Engaging the learner in the process will keep them willing to learn in future experiences. If the learner walks out of a debriefing saying "wow that was long" or "that was a waste of my time," you were probably lecturing after an experience. If the learner says "we could have kept talking for hours" after a debriefing, you have engaged them in reflection after an experience, and they are willing to learn.

Experiential learning reflects a cycle of Concrete Experience, to Reflective Observation, to Abstract Conceptualization, and finally back to Active Experimentation (Kolb, 1984). There is great depth in both the framework and terms Kolb has outlined, but they can be difficult for someone first learning the process. As and adaptation of the model (although it loses some of the nuances) would be Do, Reflect, Think, Re-Do.

Simulation is the doing component (and may be the re-doing element) allowing debriefing to be reflecting and thinking. The experience itself is not where the bulk of the learning is, as it requires reflection, thinking and re-doing to make a sustained change to a learner's mental model.

Simulationists often focus on how to make a better experience (improve the scenario, realism, fidelity, etc). Just as much time and effort needs to be placed on all areas of the experiential learning cycle for effective learning to occur. Reflecting and thinking usually occur during debriefing but we often are lacking a Re-Do period.

A debriefing that is double or triple the length of the scenario is a generally accepted rule of thumb. In actually it is not far off, but given an hour, we should plan on 15 minutes for each area (Do, Reflect, Think, Re-Do). Depending on your experiential learning style (Learning Card 3a), facilitators may want to spend more time in one area than another (for example ‘cramming in’ 4 scenarios in an hour without a debriefing as ‘doing more’ is their preference).

Understanding the Learning Outcomes Model and Experiential Learning helps a debriefer to have a foundation for effective facilitation of learning. To reach a variety of students and ensure that the learning changes practice, a more even approach is required that not only takes into account all four steps of the Experiential Learning Cycle but also all three areas of the Learning Outcomes Model.

This part of a series called “Learning That Works” by Jay Zigmont, PhD, CHSE-A (jay.zigmont@gmail.com). For a video on this topic and more information, visit http://L1.LearningInHealthcare.com. The principles above are part of the core content (Learning Cards 1, 2, 3 and 4) of the Foundations of Experiential Learning Manual (available at http://FEL.learninginhealthcare.com )

Source: Learning in Healthcare

Share: